“Johnny Marr got hit with a pint straight away. After the show we said, ‘That guitar is too fancy for touring with us!’” Stolen offsets, iconic bandmates and Coco Chanel’s advice – how the Cribs learned to be the best versions of themselves

Ryan and Gary Jarman remember Steve Albini as much nicer than you’d think, share the crazy story of a missing Mustang, and tell us how a Tube Screamer can make a guitar sound like a synth

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

At first glance, Beyonce and Lil Yachty collaborator Patrick Wimberly might not rank highly on your list of potential producers for The Cribs – but on new album Selling A Vibe, the UK indie stalwarts felt it was time to surprise themselves.

“The idea that working with somebody like Patrick would seem unusual for us is actually a little bit distressing,” says bassist Gary Jarman. “Because we never envisioned ourselves to be a raw rock band; we're very hook-oriented.”

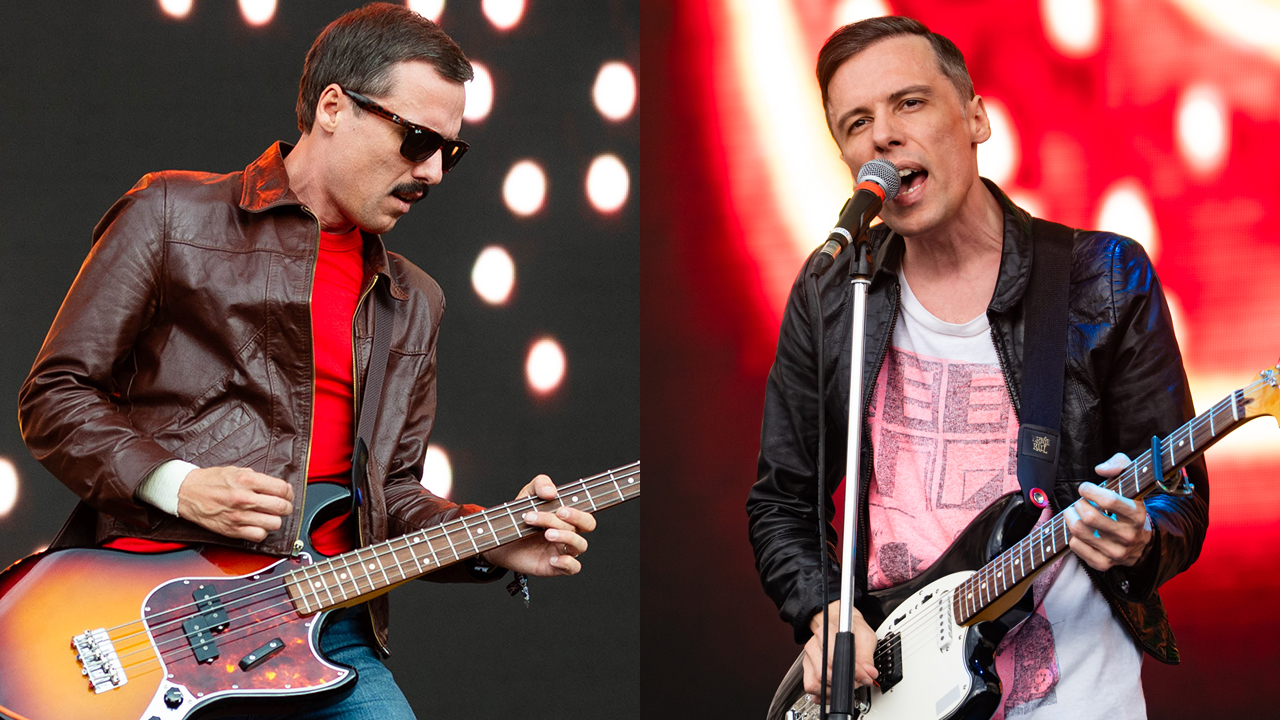

The trio’s own idea of who they are has often contrasted with wider perception. Formed in Leeds, UK, by twins Ryan and Gary, plus brother Ross Jarman (on guitar, bass and drums respectively), they arrived in the last gasp of the old record industry and were slung in with the indie sleaze movement.

Article continues belowHowever, hailing from Northern England – and far removed from the industry tastemakers, drug-takers and nepotism that came out of ’00s London – they’ve fought an uphill, DIY battle against the unwritten class system of the British Phonographic Industry [this is still the name of the UK industry body, in the year 2026 – Ed].

“We grew up without much money and so we just used whatever we had at hand and tried to make it sound good,” explains Gary. “We always got called a lo-fi band. It was frustrating, because to me, all the records deemed lo-fi are by people who don’t have much stuff trying to make it sound as good as they possibly can.”

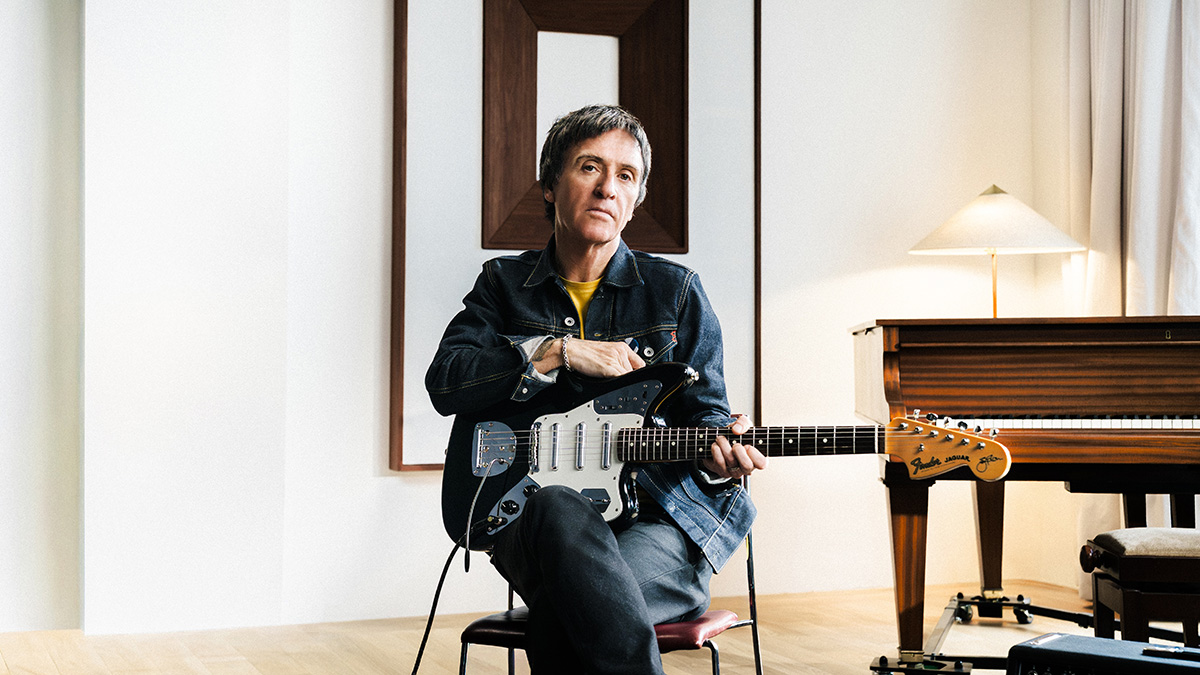

Still, success has brought its rewards; and the group have gone on to make albums with their hero Steve Albini, produce Squier signature guitars, and even attract indie rock’s superstar contractor Johnny Marr to their ranks for three years.

Wimberly has his own indie credentials as one half of Chairlift with Caroline Polachek, and with Blood Orange and MGMT productions under his belt. But in contrast to what you’d expect from a big-name producer, he came in with no preconceptions.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I've got this tiny little Silvertone amp from the 60s, and Patrick loved the tone,” says Ryan by way of example. “It’s just my practice amp at home – a $200 amp that became the main amp on the record because he heard something in it.”

That and Gary’s favorite ’73 P-Bass was about all they took along. And in contrast to what you might expect from working with a big producer, the brothers Jarman describe the whole process as a “liberation”.

“You can get stuck with a degree of baggage over time,” says Ryan. “It’s good to purge yourself of all the stuff you think that you need – you don’t really need it. The most important thing is what you’re playing. All the other stuff is just a distraction or a crutch.”

What were your favorite moments on Selling a Vibe from a guitar and bass perspective?

We did our best to get out of our own way on this record. If something felt good it was like, “Alright, let's just call that done”

Ryan Jarman

Ryan Jarman: The playing in If Our Paths Never Crossed is something I wanted to get on a record for ages. When we first started the band, I figured out a way of making the guitar sound like an analog synth but without any effects, just a Tube Screamer.

It involved taking all the tone off the guitar and it was down to certain things with the pickup selector, pulling the strings and muting in a specific way. We never found a place for it on a record before, but that's what I'm playing in the chorus of If Our Paths Never Crossed.

Gary Jarman: From a bass point of view, I really like the bassline on Brothers Won’t Break. It’s really soul-influenced. The other one is Self Respect. We were in the practice room, and I said to my brothers, “What we really need is some kind of Michael Jackson thing,” and I played that line! It was off the cuff, as an example, but it became the signature line in the song.

Ryan: We did our best to get out of our own way on this record. If something felt good it was like, “Alright, let's just call that done.” Everyone has a tendency to keep working on something, thinking, “I can make it better!” It doesn’t take long until it tips over and you’re making it worse.

Gary: It’s that saying, “Look at yourself in the mirror and take one item off before going out.” Coco Chanel said that, but I think it’s a good thing to think about in music too.

We’re coming up to the 10-year anniversary of your Squier signature models. Is there any chance of a reissue?

Ryan: I've been hassling Fender for ages to bring them back. The amount of times I get asked about those guitars is crazy, and there’s been people pushing them online to do it. But for whatever reason, Fender seems more interested in making their own weird hybrids these days.

I had three, but two of them are prototypes, so I only really had one good player. I’m like, “I really need another one,” because, for me, it wasn’t just a vanity project. I spent ages getting that guitar just right. It’s the only Fender bridge – the only setup – that really works for me.

So to placate me, they made me a Custom Shop version, which is great. I’m really liking it, but I was hoping that they’d bring the signature back; so many people ask me and I never have an answer. Some people think I’m gatekeeping them, or I’ve got a big stash at home!

Like you’re sat there feeding them into Reverb every month.

Gary: Yeah! There’s an irony in that those guitars were built to be affordable guitars. That’s why they were Squiers – so people could afford a quality instrument that could be functional and look good. Now they’re changing hands for $2,000!

There was an article about how it’s the most expensive Squier ever or something – that and that baritone. The appreciation is higher than any other guitar. It’s gone from like $300. But they weren’t intended to be collector’s pieces or expensive instruments.

I said, ‘I need to double the guitars.’ Steve said, ‘You’re going against your original vision – I don’t think that’s ever a good idea’

Ryan Jarman

Ryan: That's the way I always saw it. I spent a long time making sure the functionally was there, if it was going to be someone’s first guitar. And I played those Squiers live. It’s absolutely a professional instrument. But I have no idea what the future holds for it.

Last year your friend and collaborator Steve Albini passed away. You’ve spoken previously about how he was a warmer guy than people might expect. What are your memories of him?

Ryan: One of the things I liked about working with Steve was on the first day we got to Electrical Audio in Chicago, before we’d set anything up, he asked us some questions with his clipboard. He went, “What do you want to do?” We said, “We want to record it live and we don’t want to do any overdubs.” And he was like, “Yeah, that’s fine.”

He set up, and so quickly we were hearing that sound that’s so familiar. It was always exciting for us – that sound is part of your childhood. One day I said, “I think I need to double the guitars here,” and Steve was like, “I wouldn’t.

“You told me at the start of the session that you didn’t want to do that. You’re going against your original vision for it – and I don’t think that’s ever a good idea.” I really appreciated that about him. It’s so easy to start doing stuff out of protocol.

Gary: He was a community-oriented guy. When I went in there I felt quite shy but as I come from an engineering background, I had a lot of questions for him. Steve sat me down and drew diagrams, showing me exactly what he was doing. He told me all his secrets. He was like, “If you want to take any element of this, it’s yours. This is public domain.”

Some people, especially in the music world, think it’s their thing and nobody else can have it. Steve Albini developed one of the most iconic and recognizable drum sounds ever, and he’s just there like, “Yeah, I’ll show you how to do it!”

People saw him as this abrasive character – but that’s only because he looked out for the artist above everyone else. The people writing the checks saw him as difficult because he was sincere, honest and very egalitarian. He was the absolute perfect collaborator, just a really generous guy.

Your former bandmate Johnny Marr is also known for being generous – he famously gave Noel Gallagher his first Les Paul. Did he ever gift you any guitars?

Ryan: Me and Johnny were supposed to do a guitar swap when we first started working together. I had this white ’70s Mustang as my main guitar, and he really liked the album that was on, The New Fellas. He kept saying, “We should do a guitar swap!” It was like a talismanic kind of thing as he was joining the band. Eventually I was like, “Let’s do it!”

We’d sit in Johnny’s studio all night. He’d be showing me that guitar, like, ‘Who in their right mind built this?’

Then when we were at his house I’d be like, “Come on then Johnny, what guitar you gonna trade me?” He had an amazing collection. He’d always show me this really horrible Stratocaster that had nine pickups on it! It became a joke – every time I brought up swapping, he’d be like, “I’ve got it for you here!”

Gary: It was joked about so often that you started to think, “Is this actually what the swap’s going to be?” But I think he likes that guitar now, that black Strat with all the pickups.

It was in his video for Spirit Power and Soul.

Ryan: It weighed an absolute ton! The first time he showed me it, he was like, “Look at this!” He was laughing. When I first started going to his studio, after we decided we were going to write songs together, we got stoned and we’d just sit in his studio all night. It was really fun – and he’d be showing me that guitar, like, “Who in their right mind built this?”

Johnny just released a new signature Jaguar Special – you could always drop him a line about that.

Gary: Between the three band members, we all had a little bit of input on Johnny’s first signature Jaguar. The prototype was built for touring with The Cribs because, when he first started touring with us, he was bringing out this ’60s blue Jaguar.

At a gig at Leeds University Refectory he went out and got hit with a pint straight away! After the show we were like, “Johnny, that guitar is too fancy for touring with us!”

So he got two US vintage reissue Jaguars, a white and a black one, and we changed the pickguards, and they were his workhorse guitars for The Cribs. When he was working with us on the road he started developing his signature guitar with Neil Whitcher from Fender.

Ryan: He was going to give us one of the first ones when he came through, but that never happened.

I'm spotting a pattern here…

Ryan: Yeah, I’m just going to say – don’t hold out much hope on getting one of these Jaguar Specials, know what I mean?

You guys have a lot of knowledge of the Fender offset guitars and oddities as well.

Ryan: That was because we could never afford guitars. The first thing I got was a Jag-Stang and I’d saved up for it all summer by washing dishes. But as a result of not being able to afford them, we’d spend all our time reading about them, in magazines, Fender catalogs or dial-up internet!

It was Ry’s guitar, it went missing, it was with Matty Healy in The 1975, then it went to Beabadoobee. I don't know where it is now

If you did get the money together, you needed to know exactly which one you were going to get. So we always had a fondness for the oddballs. The Duo-Sonic was the one I always liked because it was £150 from a pawnshop in the middle of Wakefield. I loved it because it was cheap.

Gary: We’d set our sights on stuff that seemed attainable, like a Music Master bass or a Duo Sonic, because they weren’t £2,000 or whatever. That’s why we wanted to make Squiers – just to evoke that memory we had as kids; something that’s cool and attainable.

Ryan: Or that '70s Mustang. Should we tell him about that?

Tell me about the ’70s Mustang!

Gary: For Ryan's 18th or 19th birthday he got a ’78 Sunburst Mustang, which was really cool. The neck was figured.

Ryan: It was like a bird’s eye maple neck and headstock. It was really weird.

Gary: It looked really cool. It was still cheap – £600 or whatever, in the late ’90s. We used it on all the early Cribs stuff. But in 2002 it got nicked after a show in Leeds, at the Cockpit, and went missing for years. Then in 2020 I was reading an interview online, and there, in the background in a photo, was the Mustang on the wall!

It had the figured maple neck and also a little bit of the pickguard missing, like Ryan’s. So I sent it to him – “Ry, is this your guitar?” He’s like, “Looks like it!” The interview was with the owner of Dirty Hit [Jamie Oborne], The 1975’s label. We started matching photographs and it looked the same. Eventually, we heard from Matty Healy, who was like, “Yeah, it was my guitar for a bit!”

Ryan: He’d used it in some of his videos [including Sex], and he was like, “I swapped it with the guy from Dirty Hit. I know all about that guitar.”

Gary: We’d given a report to the police, but it had never showed up. I suspect it was stolen in Leeds, then moved over to Manchester, where Matty obtained it, then gave it to the guy from Dirty Hit.

So I contacted the guy from Dirty Hit, and Wakefield police put together a forensic thing with photographs, showing it was the exact same guitar, and Fender verified it was the same guitar. Then Jamie from Dirty Hit was like, “The problem is I don’t have it anymore!”

He’d given it to one of their other artists, Beabadoobee and it was like her main guitar. So it was Ry’s guitar, it went missing for 20 years, then it was with Matty Healy in The 1975, then it went to Beabadoobee. I don't know where it is now; we’re still trying to get it back.

Ryan: I still want it back! It’s one of the only guitars that’s ever meant anything to me. I used it in The Cribs before we became a professional band and it sounded great. West Yorkshire Police keep saying, “We’ll go get it for you.” But I don’t want there to be a bad vibe about it.

Technically it’s still mine. But I'd feel guilty about getting it back if someone else is using it. But then I’m like, “Why do I feel guilty because it was stolen off me?” It’s just a weird thing.

Gary: Ultimately it just hit a wall. But it’d be really nice to get it back. It would be a really circuitous, cool story.

- Selling a Vibe is out now via Play It Again Sam.

Matt is Deputy Editor for GuitarWorld.com. Before that he spent 10 years as a freelance music journalist, interviewing artists for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![The 1975 - Sex [EP Version] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/xeDGfk0UJw8/maxresdefault.jpg)