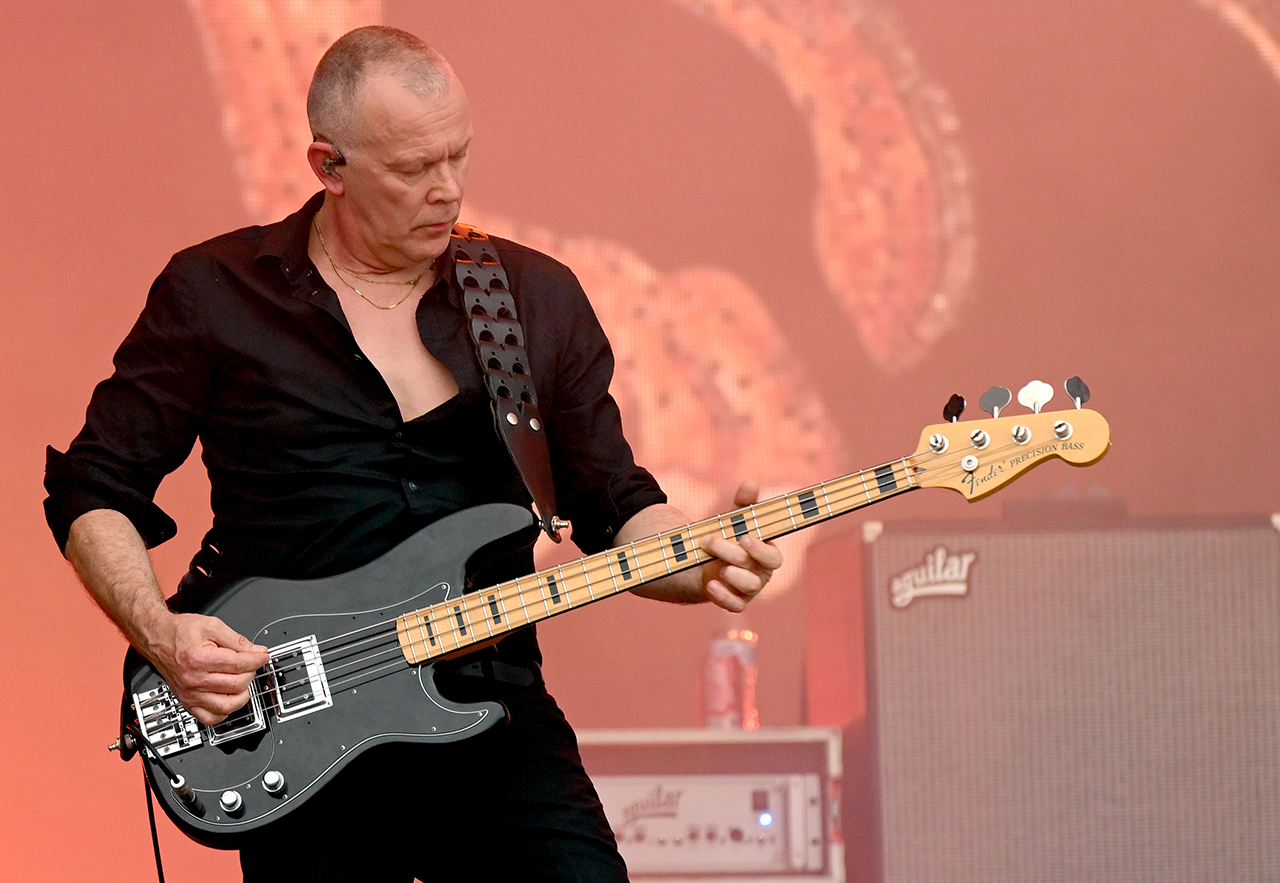

“Jimmy had his own viewpoint when he started working with Robert again. It meant having to dive much deeper into the Led Zeppelin catalog”: How Charlie Jones became the ‘other bassist’ to work with Robert Plant and Jimmy Page

He may have started in music by buying the wrong instrument, and thrown his Grammy certificate in the garbage without realizing it, but his eclectic attitude has made him a session star – and landed his dream gig with The Cult

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Charlie Jones has had long-term bass gigs with Page and Plant, Robert Plant and The Cult – but he admits his arrival in the four-string world “sounds stupid.” He explains: “When I was young I bought an ‘electric guitar’ with money from delivering papers, so I could join my friend’s band.

“I’d thought to myself, ‘Wow, this sounds weird…’ But I went to his place, all ready to go, and he said, ‘This is a bass – you’re a bass player!’ I went, ‘Okay, then…’” Luckily he took to the instrument. “I learned very quickly. Within three years I was learning upright.”

Jones has gone on to play on a host of records, most notably on Page and Plant’s No Quarter (1995) and Walking into Clarksdale (1998). But he’s also heard on records by Goldfrapp, Siouxsie, and most recently The Cult.

Article continues belowWorking with formed Led Zeppelin icons Page and Plant was, of course, “a very big deal,” he confirms. “It was very informative. I had to have a deeper understanding of blues, learn to be quick, make decisions and listen. They really worked on instinct. There was equality there; I was given freedom to express myself. Those guys were very generous.”

Jones adds: “My musical tastes are eclectic. Once I left Robert and got into Goldfrapp – a primarily electronic band – it opened up my potential further.”

What led you toward the acrylic bass?

When I started, all the basses around England were Japanese or Korean copies. Some were good, some weren’t. I used English gear – an HH cabinet and whatever else I had knocking around. The acrylic bass thing came about because I was very into glam rock, and I’d seen the Dan Armstrong basses.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

I loved them, but I couldn’t get on with the short-scale neck. Before I got the gig with Robert I was using a Fender Precision Bass. I asked Fender if they could make me an acrylic bass then, but they couldn’t – though they did later.

But basically, what led me to the acrylic bass was the desire to have a long-scale Precision Bass with the aesthetic of those ‘70s Dan Armstrong basses

What led to the gig with Robert Plant?

I’d done a record with a producer called Tim Palmer in Austin, Texas. He recommended me for that gig when I was doing sessions. I had to give Robert lots of demos I’d played on. I had a taste for crossover artists from the Middle East, and you know how Robert’s into that stuff.

He heard that, and some of the other stuff I’d done, and it was quite eclectic. That appealed to him. I wasn’t strictly a rock bass player; and, of course, Robert’s tastes are pretty eclectic.

What gear did you pair with the acrylic bass once you joined Robert?

Robert was very gracious because I didn’t have the budget to buy the type of gear I needed for the touring he was doing. I needed a good rig, but the popular rigs at the time were Trace Elliot, which weren’t for me.

I was allowed to buy anything, and I went for the Marshall Jubilee for bass because I loved it. They had these big cabinets and massive transformers, and they weren’t valve amps. They had transistors with huge headroom with no breakup, and were very focused.

Jimmy is a fantastic bandleader. It was pretty intense. It was like a big apprenticeship.

It informed my gigs live, though not necessarily for recording. I generally don’t use large valve heads; I use rigs with good weight transformers and plenty of headroom. The Jubilee series was bulletproof.

What was it like transitioning from working with Robert to adding Jimmy Page for the No Quarter - Unledded show?

Jimmy had his own viewpoint when he started working with Robert again, so there was a bit of a transition. The word "re-audition" is a bit big; but it was a different production working with Jimmy so that he felt comfortable. It meant having to dive much deeper into the Led Zeppelin catalog.

Jimmy is a fantastic bandleader. And his knowledge of the Led Zeppelin material – he’d study the bootlegs and say, ‘Hey, I wanna do this extended version of this song.’ So it was pretty intense. It was like a big apprenticeship.

And you were learning bass parts laid down by John Paul Jones, which is no easy feat.

That’s exactly right. Sometimes they’d say, “Your playing is not exactly like John Paul Jones’ on this tune. But we like it, so stick with what you’re doing.“ They were flexible. As long as it was working, they were happy.

My manager said, “Your Grammy certificate’s come through.’ I had to go outside to the garbage bags to find it

They weren’t necessarily trying to do a reproduction of Led Zeppelin, because that’s not possible without the original rhythm section of John Paul Jones and John Bonham. It had to be genuine, and that meant adding a bit of your own flavor to it, and they were open to that.

Which led to you working on Page and Plant’s collaborative album Walking into Clarksdale.

That was different – when we did the Unledded record it was a huge Egyptian-style ensemble. We’d just get our heads together on the spot. But with Walking into Clarksdale we had to go into a room and write together. Writing with those guys was very organic. But it was no bowl of cherries!

Notably, you co-wrote Please Read the Letter during those sessions.

We rehearsed and wrote a rough arrangement for it. Then when we got to Abbey Road, Steve Albini was producing, which was a thrill for me. That was crafted between all of us, meaning we all had big input on the song. Robert took the lead in terms of the top line, and how the chords would fall within the arrangement, but I always believed it was a special song.

Still, it must have been a surprise when the song netted you a Grammy after Robert re-recorded it for his Raising Sand album.

Truthfully, it was! I was in this weird situation. I’d come off tour and said, “I’m not gonna open any of my mail for three months. I don’t give a shit. I don’t care what comes through. I’m shutting myself away.” Then my manager called and said, “Do you realize you’ve got a Grammy for this song?”

A lot of musicians think acrylic bass is a novelty or an oddity. I understand that. But it really does have a sound I love

I went, “Really?” My manager said, “Yeah; your certificate’s come through.” I had to go outside to the garbage bags to find the certificate ‘cause I’d thrown it away! So it was a surprise; but to Robert’s credit, he always had a vision for that song and it never dwindled.

In 2022 you had the Fender Custom Shop build you an acrylic bass. Is that now your main instrument?

Yes, but it lives in America. I love that bass; it’s a copy of a ‘70s Precision. I found that some of those old basses from ’75 to around ’80 are slightly heavier, with thicker necks. They really lend themselves to rock compared to the '60s basses. So I had Scott Buehl copy that.

He made it lighter than the one I’d used with Goldfrapp, which weighed a ton. He chambered it, so it has a different sound. I use that one a lot with The Cult paired with Aguilar amplifiers and cabinets, but I leave it in the States. When I fly home, I use a ‘70s-style Antigua or a flat-body Precision.

Not everybody takes the so-called “plastic basses” seriously, but you’ve done a lot to alter that way of thinking.

I can’t be specific, but you assume a lot of musicians don’t take the instrument very seriously. They think it’s a novelty or an oddity. I understand why people think of it like that. But it really does have a sound, and I love that sound.

It doesn’t fit solely into one genre. Combined with the visual aspect and working with lots of different artists, it made my viewpoint as a player. You can’t pigeonhole what I do. That’s always been the case, and I’m happy about that.

How did you get the gig with The Cult?

It was kind of a homecoming because I’ve always loved The Cult; I always wanted to join, or at least do some recording with them. Tom Delgety, the producer, asked me to play on Under the Midnight Sun, and I got on so well with them that they asked me to join. It’s great – but I really had to concentrate on playing with a pick again.

The Cult have announced a hiatus from touring. What’s next?

I don’t really know what’s next for The Cult. I think they’re gonna take this time out, and there’s maybe some box set coming out of the Death Cult and Cult material from Beggars Banquet. And they may well want to do some recording, so that may happen this year.

Other than that, I’m gonna be doing my own stuff, and some other sessioning and recording. I’ll be concentrating on my bass playing, working hard to dig deeper into the lane that I’m in.”

- Stay up to date via Jones’ website.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.