“David Bowie had to mix him out of his own song because Tom drove him nuts in the studio”: Richard Lloyd on episodes with Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix, and his bittersweet relationship with Tom Verlaine

They lost touch long before Verlaine’s death, but now the guitarist is at peace with those adventures. He reflects on Television, and his memories of backstage lessons with Jimmy Page's tech, and an onstage jam with John Lee Hooker

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Like many of his generation, Richard Lloyd was moved by The Beatles during his early guitar journey.

“I recognized that the guitar was their magic wand,” Lloyd says. “They were casting a spell over young people. It’s an impulse that never left me.”

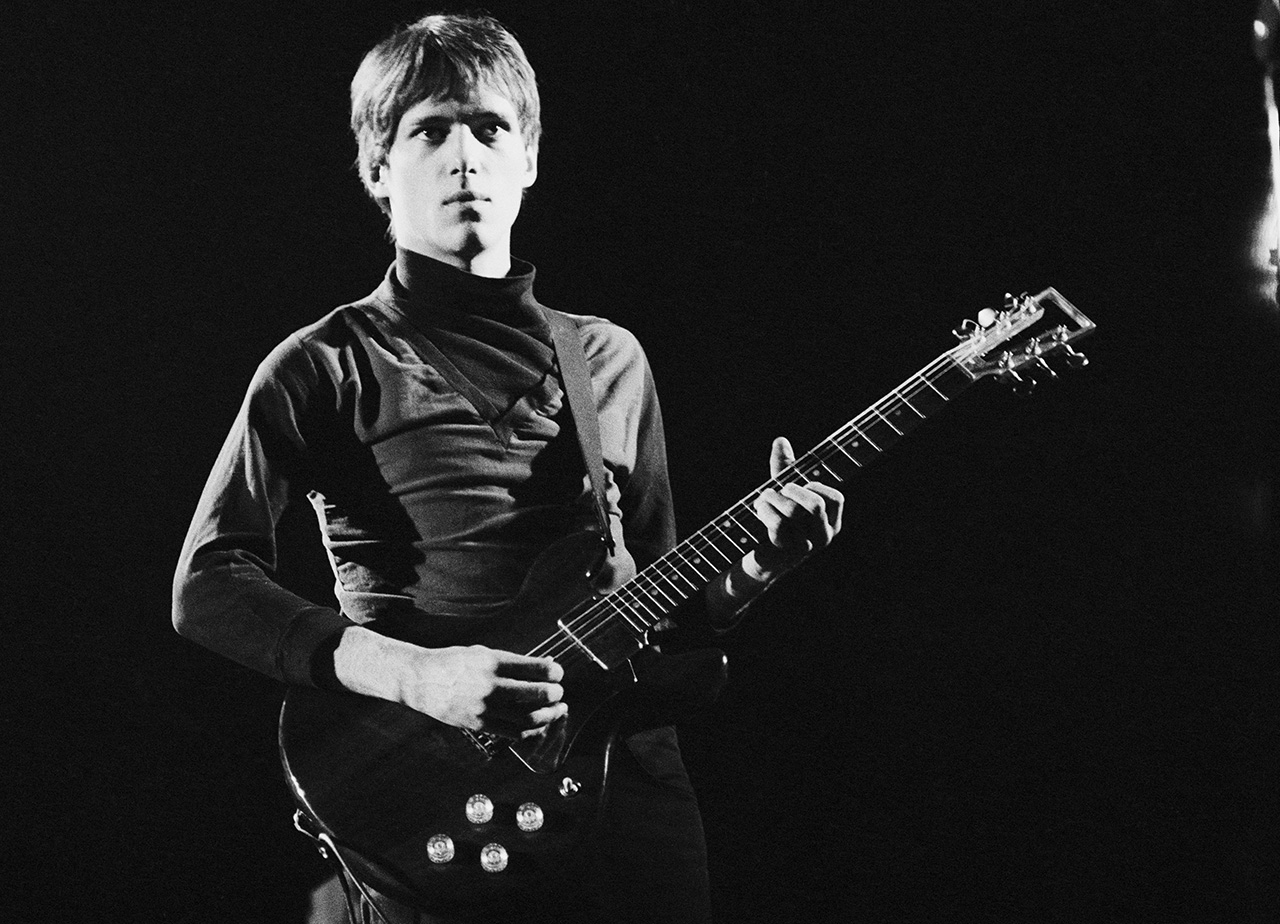

With Tom Verlaine, Lloyd went on to cast spells of his own with Television. Songs like See No Evil, Marquee Moon, and Friction became punk-meets-art-rock guitar anthems.

“We were like the glamor of poverty,” Lloyd says. “We looked like runaways playing rock ‘n’ roll.”

Musically the pair were a match made in heaven – but personally they were plagued by decades of turmoil. “Dynamic tension existed, and that was responsible for a great deal of the creativity,” the guitarist says.

“There’s no denying that Tom was a genius. He was a poet. I’m not poetic. His double- and triple-entendre was better than mine. But in the realm of our magic, my guitar playing was on another level, though he could play and sing. It satisfied me.”

Verlaine died in 2023, and Lloyd hadn’t kept in touch. He’s okay with how things turned out.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I wanted to make a dent in rock history. That was my goal, and that came true.

“We made a difference with how rock was thought of. I’m proud of that. Tom didn’t want to talk about that… he thought he was above mentioning the past. But I’m extremely proud. I know we made a difference.”

Did you choose the guitar, or did it choose you?

It chose me. I was playing drums first. I have synesthesia, so the cymbals had a color different than a snare drum – stuff was very lively. One day I was playing, and the color went out of the instrument. The drums sounded nothing like they had before.

They went black, grayscale. Then a voice announced in my left ear, ‘You gotta play a melody instrument.’ I tinkered with the piano but nothing ever came of it – I knew one note sounded good and two notes sounded good together, but three notes, I couldn’t figure it out. I still don’t like the piano much.

Around 1958 I went over to my cousins' for a sleepover, and they passed around a guitar. I got my hands on it and just fell in love. They wanted to go to sleep, so I went to the bathroom and played three chords until there was a knock at the door: “Get out of the bathroom!” I’d played those three chords all night long.

Did you take to it quickly?

The guitar was a powerful motivator. I began trying to bend strings, and I wanted to go electric right away. I’m not fond of acoustic; it doesn’t suit me. I have one, and I can play.

I’m drawn to electricity – when I was four or five, I pulled a plug out halfway, grabbed it with my licked fingers, and got a shock all the way up my shoulder. I wanted to know what electricity was, and I sure found out!

I recognized Hendrix’s voice on the phone. It was immovable. You couldn’t disguise it. He had a particular way of speaking

I found it’s a ruthless, uncaring energy that wanted to go through me and evict me from my own body. It caused my arm to buzz for two weeks! So I knew what electricity was, and the guitar and electricity were mighty fine.

As you grew older, you met a musician named Velvert Turner, who claimed to be close with Jimi Hendrix.

He was a scrawny black kid and he wasn’t dressed spectacularly. Everybody laughed at him. One of the kids asked him, “You know Jimi? Prove it!’” He said, “Well, he’s in New York because he has a show later. I could call him at his hotel.”

He went into the other room and dialed a number. It rang, and he asked for a name other than Jimi’s. We proclaimed, “You didn’t ask for Hendrix. Who’s this other guy?” He said, “Jimi doesn’t register under his own name.”

He handed the phone off to the guys, who handed it to me, and while I was on the phone, Jimi picked up and said, “Hey, man, who is this?” I said, “It’s Velvert, Jimi,” and handed the phone back.

Was it actually Jimi Hendrix on the line?

John Lee Hooker said, ‘I’m gonna call you up on stage. You’d better come or I’ll chase you down!’

I recognized Hendrix’s voice. It was immovable. You couldn’t disguise it. He had a particular way of speaking. So this was the verifier. But he took the phone, talked to Jimi privately, hung up, and said, “Jimi is playing tonight in town. I can bring one person.”

He did a little pirouette, pointed at the sky; and when he brought his hand down he was pointing at me. He said, “I’m going to take you.” I never found out why he picked me, but I assume it’s because I believed him when nobody else did.

Is it true that Jimi was teaching Velvert guitar, and that you picked up some tricks too?

It turned out that Jimi considered Velvert his little brother. He was teaching him to play electric guitar at an apartment on 12th Street. Velvert would call me because I lived six blocks away.

I had a guitar by then – a Stratocaster named Samantha. Velvert would come over and show me what Jimi was teaching him. Things like double stops, bends, octaves, and little things that I picked up on because I have a photographic memory.

I couldn’t play them for a couple of years, but because of my memory, I had them locked up in there. So many of the things I was trying to accomplish came way down the line, but it didn’t matter to me. It was one of the funniest periods of my life. We hung out a lot.

Through Velvert’s Hendrix connection, you met and spent time with Led Zeppelin and many others.

I’m starproof – I wasn’t in awe of anybody. I’d tried to learn from their records, but I wasn’t very good at that. I can repeat what another person’s hands are doing, but I can’t repeat from ear; I learn by sight.

You were invited to a Led Zep show, weren’t you?

I’d turned Robert Plant on to some very good hash, and they invited me to bring some to a show! Before it started I asked the guitar tech if he would show me what Jimmy Page did to warm up.

He got all excited, took me to one of the vacant rooms backstage, and showed me a bunch of stuff. Like I said, I’m very good at picking up what’s played in front of me. I got a lot out of that night.

Before forming Television, you sat in with John Lee Hooker.

One thing I learned then was that, if you keep your mouth shut, you’ll survive a lot longer in delicate social conditions. John Lee Hooker was playing in Boston, where I was living. I went backstage, entered the dressing room, sat down, and didn’t say anything.

John Lee Hooker was working with someone, then he turned to me and said, “Sonny, what you do?” I said, “I play guitar.” He said, “Are you good?” I said, “Well…” He said, “No, you’re great, man! I’m gonna call you up on stage. You’d better come or I’ll chase you down!”

David Bowie had to basically mix him out of his own song because Tom drove him nuts in the studio. But Bowie could bury his parts, or not hire him again. I couldn’t do that.

He told me, “I’ll tell you the secret of playing electric guitar.” I went over to listen and he said, “Bend the strings. Learn one string, how to go up and down, bend the notes, and shake them until the woman go, ‘Whoa!’ and the man go, ‘Ahhh!’’’ That’s a literal translation. Since then, I’ve been bending and shaking the strings.

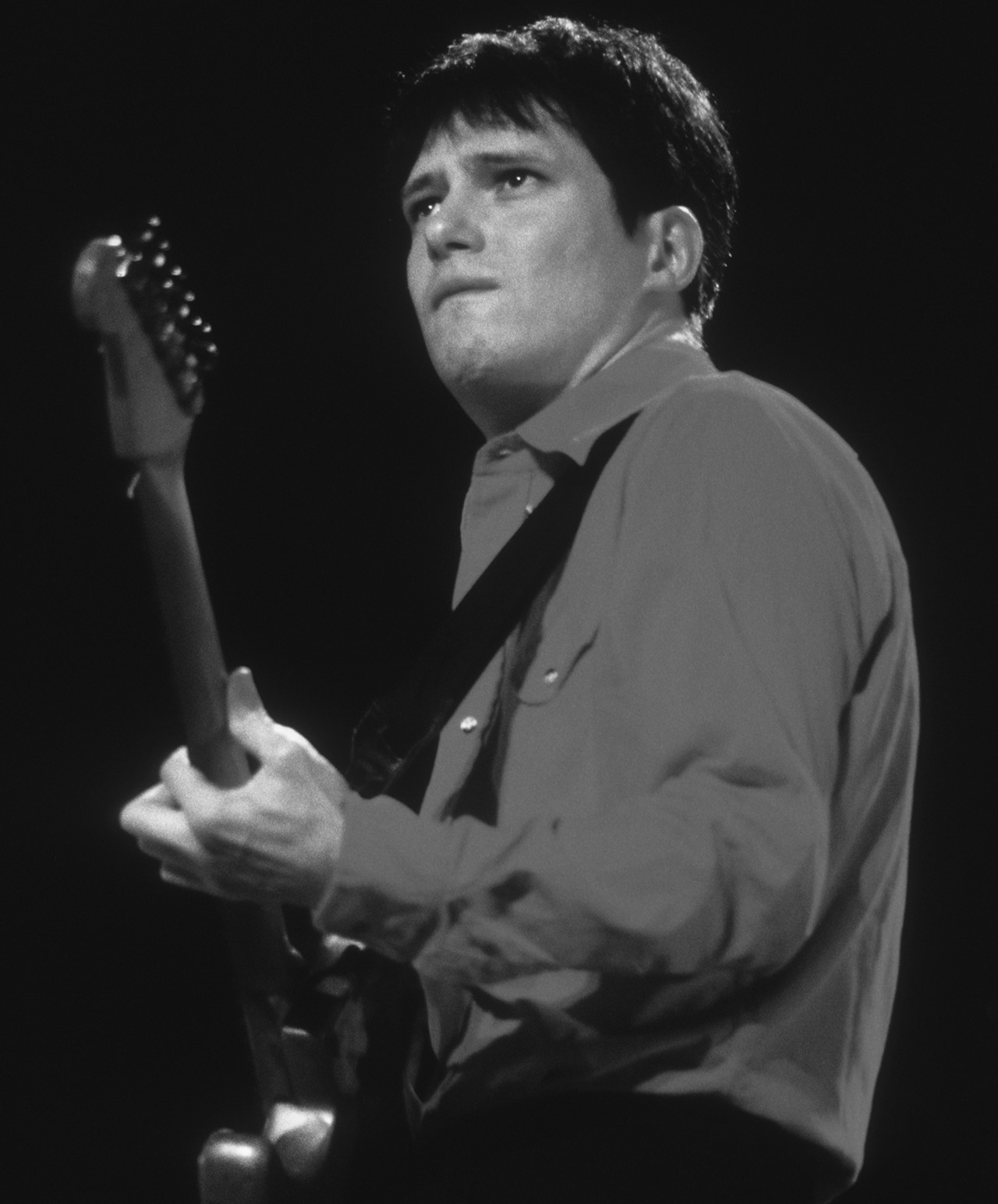

How did you meet Tom Verlaine?

I’d never had a band. I didn’t want to be in a band until I found something I could really participate in. I wanted to be surrounded by something that you can’t describe. I was hanging around Max’s Kansas City, where I met [manager] Terry Ork.

He said, “Do you want to see this guy Tom? He plays solo electric guitar like you do.” I said, “What good is it for me to see him when I could be practicing?” But that day one of my strings had broken, so I told him I’d go to see this guy.

When Tom turned on his amp – one of those really old Fender amps that thumped when you turned it on – the club manager told him to turn it down! After he did his songs, I turned to Terry and said, “Forget putting a band together around me. Hook the two of us up.”

I said, “With Tom and myself, you’ll have a history-making something. You’ll have a band you want to manage.” So Terry sponsored Television. Neither of us had amps at the time, just electric guitars, so he bought us a couple of Fenders and let us rehearse in his loft.

We passed the guitar back and forth. Then Tom went off to the side and muttered something, came back, and said, “Yeah, let’s try it.”

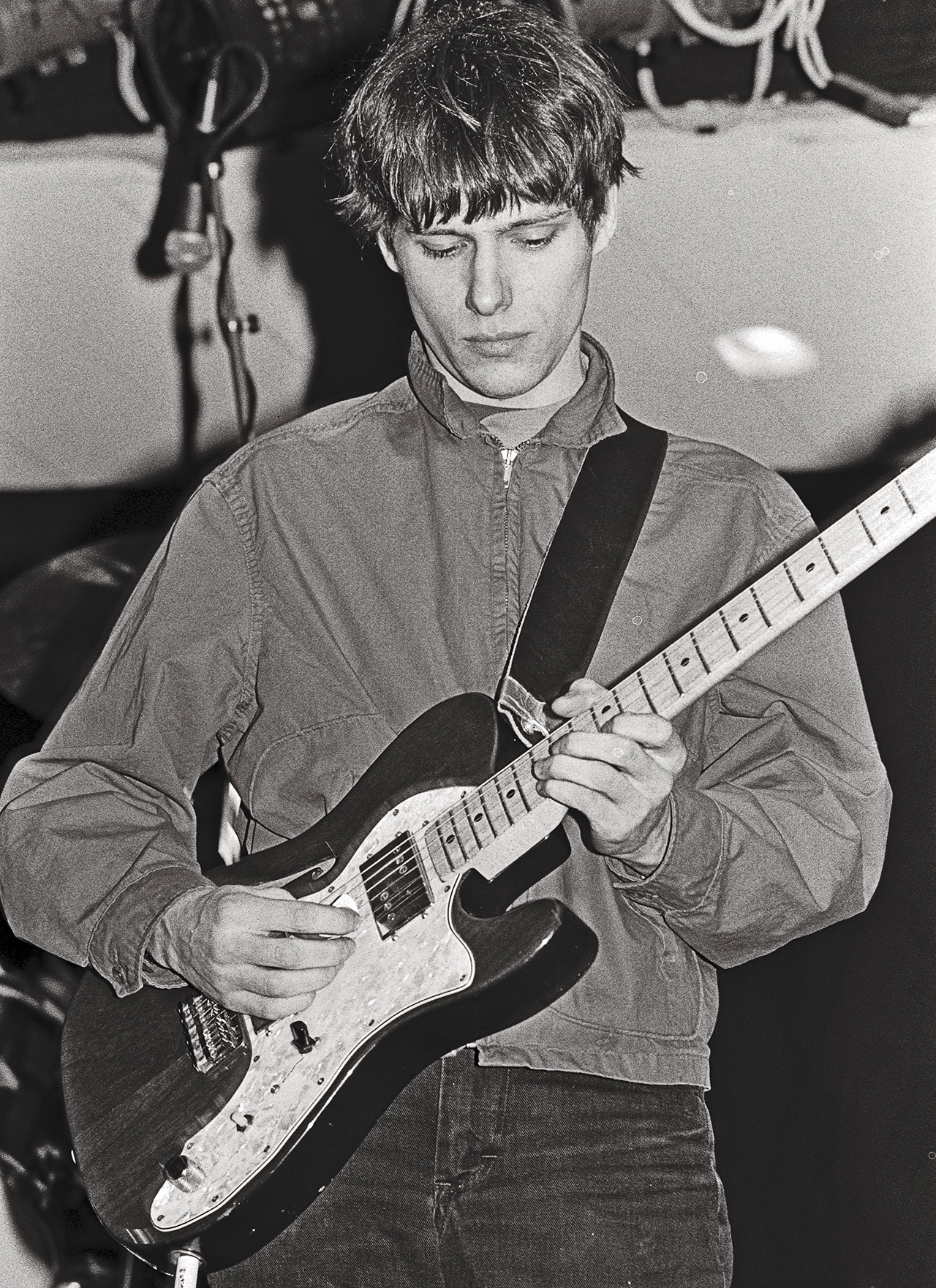

One of your main guitars back then was a pinstriped Tele. Where did you get that?

It was an amazing guitar. I couldn’t afford a Strat, but I scraped up enough money by selling my drum kit and went with the Telecaster because Stratocasters were $100 more. I bought the Telecaster with a rosewood ‘board.

What do you remember about putting together songs like See No Evil and Marquee Moon from Television’s debut, Marquee Moon?

Those are songs we did in our live act. In the beginning, with Richard Hell [on bass], it was very slaphazard musically. But when Fred Smith took over after quitting Blondie – which was considered a smart move because Blondie were not well-respected compared to Television – things changed.

When we went to record I had these lead parts for the verses at the beginning; I had most of that stuff. But the song Marquee Moon didn’t come until much later. I remember rehearsing it and playing it.

With See No Evil, Tom was fooling around with octaves, and I came up with the rest. There have been debates on that – I didn’t get a penny for the songwriting, nor the other ones that I was responsible for. A real drag, because publishing is where you can actually make a living.

I fought him over See No Evil and Friction, but he went behind our backs – you’d find out he put it under his own name

Why is that?

Tom went by the argument that everything is the melody and the lyrics, and that there was nothing deserving of credit for what he called “the arrangement.” I debated that. For instance, with Guiding Light, I wrote the part that runs through the whole song.

That was the final straw. I said, “You’ll either give me credit for this, or you can come up with something else because I won’t play it if you don’t give me credit.” I got half credit on that.

I fought him over See No Evil and Friction, but he went behind our backs – you’d find out he put it under his own name.

Did that make it hard for you to stick around for another record, which turned out to be 1978’s Adventure?

I’d say so. But it was hard for both of us. Tom wanted to be everything. He was gonna head out on his own because he figured he’d make more money. That’s all that motivated him: the almighty dollar. I call him a nickel-nursing, penny-pinching thief.

I created this thing. I said to Terry, “Put this guy and me together.” It was me who came up with the notion that I’d be the lead guitarist, but that we’d split solos. I played the leads anytime that Tom was singing. And that was most of the damn song.

Things like Friction, I came up with that bottom line, and it never varies for the whole song. It’s the ground upon which it’s built, and I never got credit for that. That sucks.

Is that what led you to make your solo album, 1979’s Alchemy?

Not exactly. We were both straining. I wrote songs, but none of them fit Television; I recognized that. I tried to present ideas – but when I did, he took writing credit for the whole fucking thing. You have to say, “Does the benefit outweigh the negatives in sticking around? Am I better off somewhere else?”

For 35 years, Television was my number one priority. Even if I had stuff going on, if Television looked like it was going to get together or do something, I’d abandon my own works.

Seeing that Tom didn’t feel the same way, do you regret that?

Well, I’m already a manic depressive – bipolar A, as they say. Every time we went into the studio, Tom would literally drive me nuts. He would act in such a way that I would end up in the mental hospital, or just the regular hospital.

What sort of things would he do?

There’s no answer to that. I don’t know anyone who’s ever worked with Tom who’s not completely distraught by his lack of cooperation with anybody or anything.

I remember his sense of humor, which was outstanding. His personality had good elements. I loved being around it – as long as we weren’t making a decision about anything

Even David Bowie had to basically mix him out of his own song because Tom drove him nuts in the studio. But Bowie could bury his parts, or not hire him again. I couldn’t do that.

So you and Tom had lost touch before he died?

We didn’t keep in touch at all. After I left, that was that. We were together basically 24 hours a day when touring and making records, and it was a great, fantastic, laugh fest. We had a good deal of fun together, but it didn’t reach our personal lives. We’d only meet up when we were making music.

How do you remember Tom?

I remember his sense of humor, which was outstanding. He nearly brought me to piss with his jokes and tomfoolery. He wasn’t above making fun of himself, so his personality had good elements.

I loved being around it – as long as we weren’t making a decision about anything. If we were coasting along, he was fabulous to be with. He had another side.

What’s next for you?

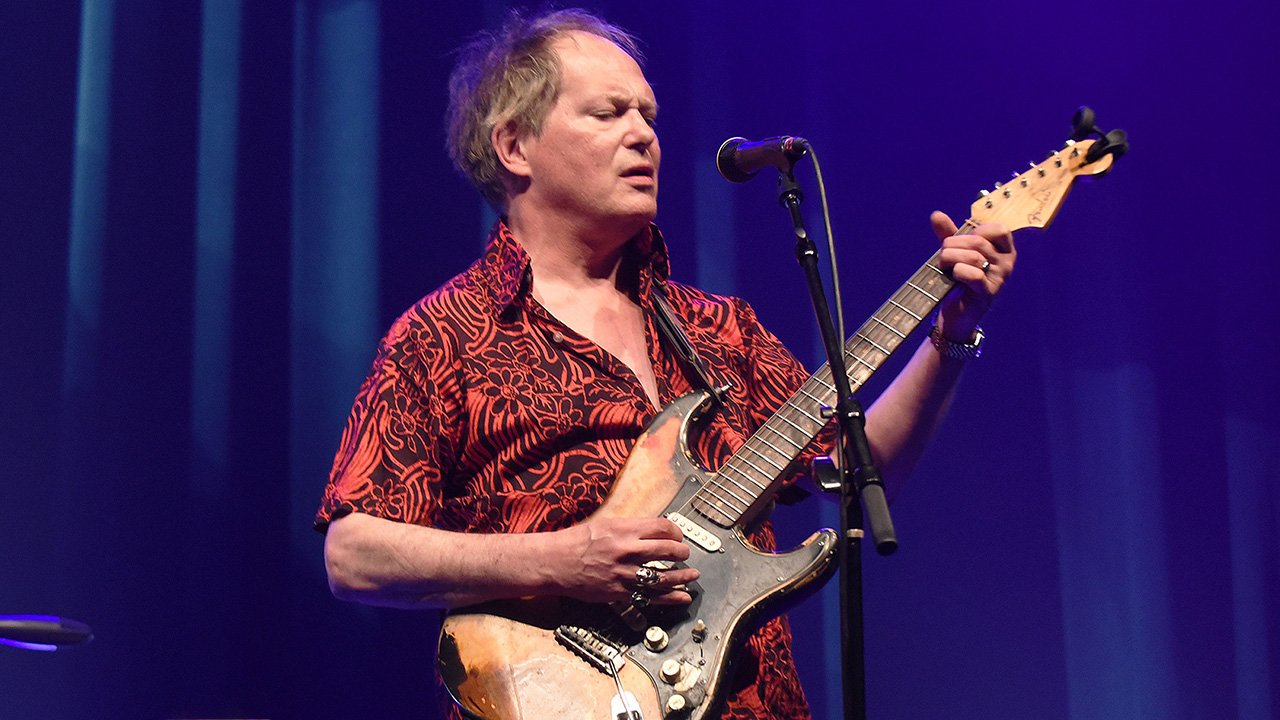

I have a tour coming up in the Northeast and Midwest as The Richard Lloyd Group. We’re a trio, which suits me. For many years I wouldn’t touch Television songs.

But as the last functioning member of the band, I have a responsibility to the fans. I play a number of Television songs, my own songs, and some covers, so everybody has a good time.

- The Richard Lloyd Group’s current tour runs until January 24.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.